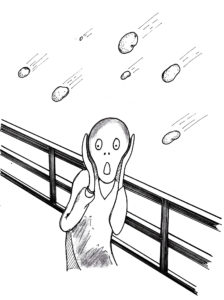

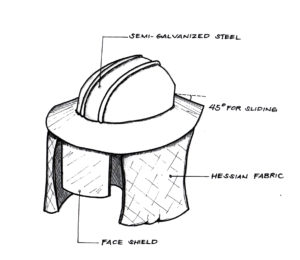

It was raining potatoes. Again. The fourth potato storm of the season began with a starchy rumbling in the clouds. As the brown clods cascaded from the heavens, locals rushed indoors and covered their ears with headphones. Loud clunks and thunks reverberated in households across the city as the tubers pelted sheet metal roofs, sounding off in a carbohydrate chorus. Umbrellas crumpled. Roads closed down. Classes suspended. And the few unlucky souls who dared brave the deluge without a Department-of-Health-approved helmet had to be rushed to the emergency room amid disapproving glares from medical staff who silently judged the numbskull who fancied himself invulnerable.

“Tigas kasi ng ulo.” they would sneer.

It had been forecasted anyway, which made it harder to sympathize with those who did not take cover or take the necessary precautions. For the record, this was the third year that potatoes rained from the sky. The present reaction differed significantly than how it had been when it first happened. Meteorologists were dumbfounded. Doomsayers proclaimed the Apocalypse had come. Atheists countered that the Bible said nothing about potatoes, while Agnostics still didn’t know what to believe. The President declared a state of emergency while every single keyboard scientist argued about its merits and causes on social media. Shrines to potato gods began to sprout along the Halsema, first in Atok and eventually reaching as far as Bauko. Various media outlets, local and international, flocked to Baguio only to be met with one-word replies from weary locals who were tired of the same questions posed by different make-up caked faces.

“Totoo bang umulan ng patatas sa Baguio?”

“Did you really see the potatoes fall from the sky?”

“What’s your favorite potato dish?”

The once enthusiastic yeses eventually transformed into quiet nods which inevitably turned into grunts. The media had a field day until it got tired of the whole thing, and like most pieces of old news, the strange phenomena went from being front page material to getting filed underneath gossip news about Piolo Pascual’s latest rumored romance.

Such was the way of the world.

Economically, the entire commotion single-handedly wrecked the Buguias farming economy. Children no longer sang “No minas ti patatas, mapan kayo ijay Buguias” because cropping communities ignored the plant altogether. Prices dropped to the point that even the lowly sayote cost more than ten times its amount in potatoes. Tourism has shot up at least, mostly from wannabe storm-chasers clamoring to get a first-hand look at the potato-ey precipitate. Of course, 80% of the ER cases were of these amateurs who often had little regard for Mother Nature’s patatas powers.

“Tigas kasi ng ulo,” the locals sneered.

And like most things free, abundant and natural, potatoes lost all value in society. Dishes that featured the tubers suffered such severe backlash that establishments began banning french fries to appease the masses. Restaurants with remaining stock tried to give them away for free, to which locals declined. Giving someone a potato became a most profound insult, akin to cursing the recipient’s family ten generations over. The evening news once reported a man going on a violent rampage because his workmates gifted him a sack of potatoes on his birthday as a prank. Five people were hospitalized, including the attacker, who in his rage walked out in the midst of a potato shower without a helmet, because of course, justice must be served in the most poetic of manners.

And so potatoes continued to fall from the sky. And it followed that everyone stopped caring for them. Potatoes lined garbage cans and were cast off entirely from any role in society. This type of denial worked for the locals until it began raining money a few months later.

Copyright © 2018 Cousin from Baguio